The first time I met Fr. Edwin Leahy, I had something I needed to make happen. I needed him to perform a miracle and he had turned me down. Father Ed is a Benedictine monk, who is headmaster of St. Benedict’s Preparatory School, one of the most successful schools in the world, successful because, in a city where only 20% of students graduate from high school, more than 98% of St. Benedict’s boys graduate and more than 99% of the graduates go on to college. All these boys come from the same tough streets that all the other kids in town come from. The only difference is they have Father Ed. And, alongside him, the amazing staff of the school, and thousands of alumni who have graduated from the school since it reopened in the early 1970s following the 1968 riots in Newark.

So, on a trip to New York, I took the time to cross the river to Newark and track him down. The headmaster wasn’t in his office when I arrived, so I took a walk through the school with my friend Brendon McKeown, a colleague who also volunteers as the goalie coach for the school’s championship soccer team. It was Brendon who first told me about the school and the culture of success they had built. Based on what I’d learned, I knew Father Ed could help one of my clients with a problem.

We found Father Ed halfway down the steps to the playing field, talking to a knot of students. He was dressed in his traditional black Benedictine tunic. He was in his early 70s at the time but looked closer to 55. He apologized for being late as we walked into the building.

“I can’t run this school from my office,” he explained. “When I started out, I started managing by walking around. I didn’t know that was what I was doing. But I had to see what was going on. So, whatever’s in the book that says where I’m supposed to be, sometimes things have to wait, because at any given moment there might be something that needed my attention.”

Leadership happens when people can look at you and say, “I feel OK with this person. I can be vulnerable with them, I can be honest, I can be open.” And when you watch Father Ed walk through the school you can see that happening with the kids. They’re willing to trust him. In a world where maybe they’ve never been able to trust anyone before, suddenly here are adults they can trust.

As I followed him through the hallways filled with young men on their way to their next class, I could see his head searching their faces and reading their body language, intensely curious about what they could tell him about what wanted to happen in their lives. And with teenage boys, mistakes in judgement can happen fast.

We found a teachers’ common room and sat down. I told him why I was there.

“My clients run a large organization of Catholic hospitals. They have to take care of anyone who walks in the ER, whether they have insurance or not.” It was just after the Affordable Care Act went into action in the United States, and there were provisions that required them to expand their care not just to patients who showed up at the hospital but to the population at large. They were being compensated if the health of the population improved, and that meant they had to get upstream on problems like teen pregnancy, street violence, homelessness, and poverty.

“It feels like an impossible challenge,” I said. “We need them to hear from someone who’s already done the impossible. I need you to show them what a miracle looks like in real life.”

I asked him how he dealt with kids who lived on the same block with gang members, who heard gunshots on the street and sometimes saw people gunned down. “Other kids they grew up with are now in the gang; how do you keep them in school?”

“I tell them they’re in a gang, too,” he said with a laugh. “The St. Benedict’s gang. And they have to take care of their brothers.” As he talked, I remembered a quote I’d heard from the author, David Shields. “It’s all about the undertow,” he says, meaning you’re always being pulled under by the deep ego that’s weighing you down with negative, self-hating thoughts. It’s always about the ego trying to sink you, to make you feel unloved and unworthy, to make you believe you’re not big enough to win.

How does a teacher overcome the undertow? “You have to believe that love wants to happen. Growth wants to happen. The right things want to happen for everyone, and they will if we can get out ahead of the problems just a little bit.”

He explained that even with boys who don’t finish school, their time at St. Benedict’s is, as Father Greg Boyle in Los Angeles would say, tattooed on their heart. “Even boys who only stayed for one year, when we have a reunion, they come. They’re part of the family.”

He told me about a former student who got involved in a murder and spent 35 years in jail.

“Yes, he messed up. But he didn’t stay messed up. And when I have a kid who’s on the verge of making a bad decision, I get him on the phone with the boy and he talks to them. Maybe twenty minutes, but he always walks them back from the edge. When the kid hands me back the phone, we’re good again.”

A few months later, Father Ed spoke to my clients, an audience of senior hospital administrators, and he helped them understand that “good healthcare wanted to happen,” in spite of all the obstacles. That people wanted to live better, healthier, and more productive lives. And that their organizations could succeed in helping them do that. He made such a difference to that client company that they became a major contributor to the school.

We are put on earth for a little space

that we might learn to bear the beams of love.

William Blake

After the event was over, the Father took me aside.

“You’re an angel,” he said to me. “I didn’t think I wanted to do this. I didn’t think that I had anything to say to healthcare. But now I see that this was my calling. You helped me see that.” I’m not an angel. All I did was help him see something that wanted to happen within him and around him.

To learn more about the St. Benedict’s story, watch the extraordinary 60 Minutes segment on the school.

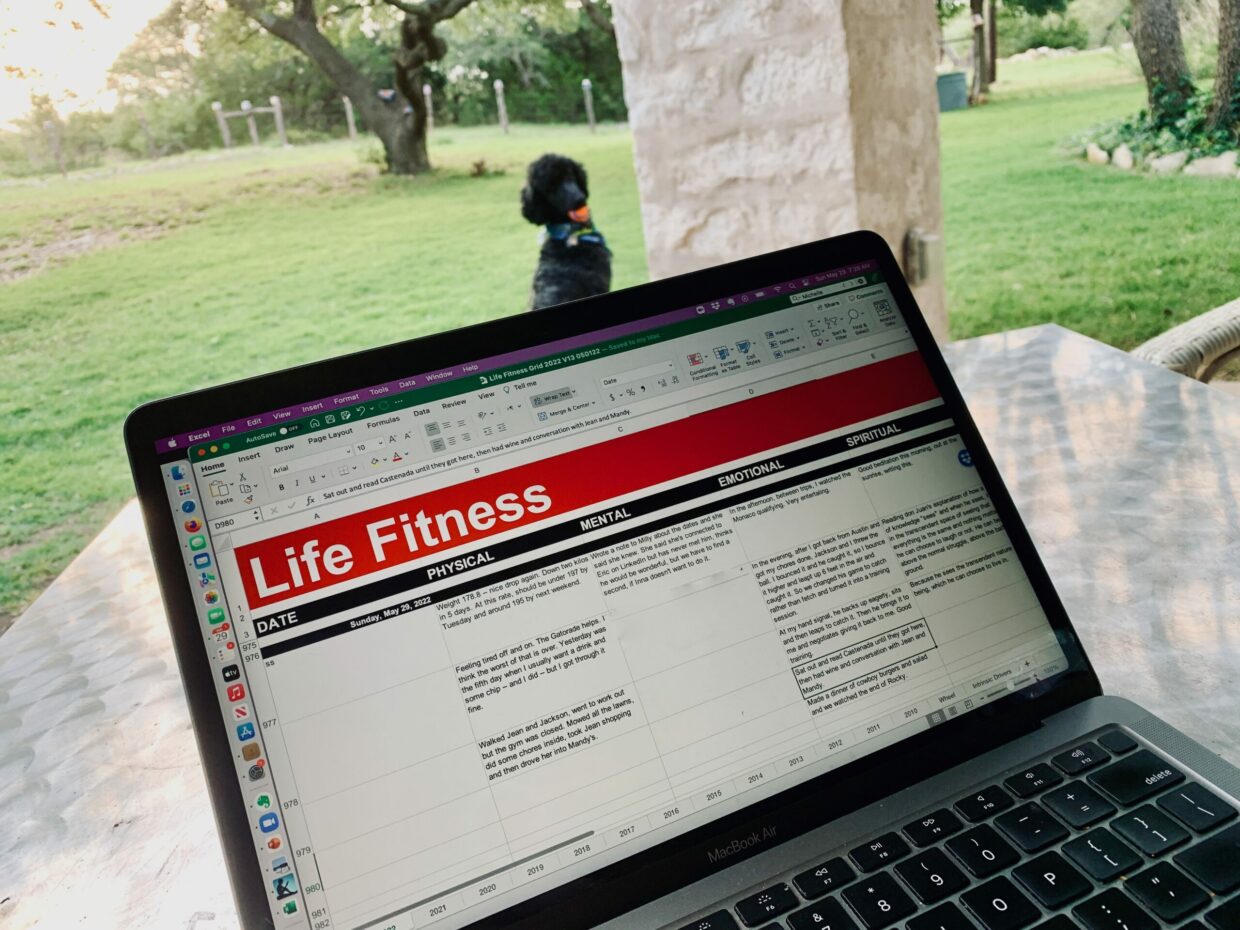

Photo credit © Michael Paras Photography